Victor and Dyslexia

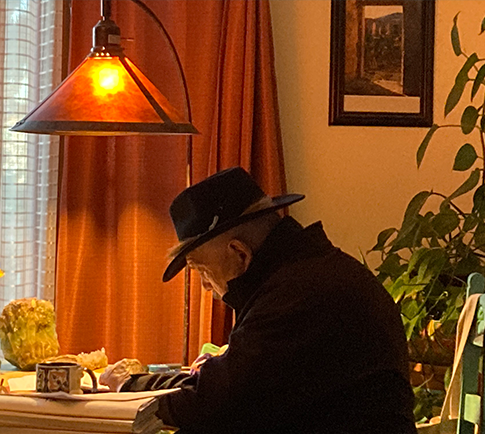

Biography

About dyslexia, I want you to know that I’m still a little bit nervous when I talk about this. I was in my mid-40s when my wife Barbara told me that a teacher told her that our two sons, David and Joseph, should be evaluated for dyslexia.

I’d never heard the term “dyslexia” and Barbara told me that this teacher explained to her that the best place to take our sons was to Long Beach, that the woman who ran the place was considered the foremost expert on dyslexia in the nation.

Well, we drove up to Long Beach and the woman took each of our boys into the back room while Barbara and I stayed in the waiting room. Then after

testing each boy, she told us that Joseph, the youngest, who was about 10 at this time, was an 8 on her charts that went from 1-20, so he would have some difficulty in reading, but not too much.

Then she told us that David who was two years older than Joseph, was a 12, so he was going to have to work twice as hard as other students to learn the same material, and yet, at his level he would still be able to finish high school and go to college and do a profession, but it was going to be difficult for him.

Well, for me all this sounded pretty good, and so I was ready for us to go. But then the woman told us that dyslexia was hereditary, and she asked if Barbara or I had trouble reading. I laughed, telling her that Barbara had been reading since before kindergarten, and I, the writer, was the one who used to have trouble, but I didn’t have any trouble anymore, and so I got up for us to leave.

But the woman now said that she’d like to test me.

This is when I began to get upset, and so I said to her that there’d be no purpose in doing this because I now knew how to read.

“I understand,” she said, “but I’d like for you to please let me test you anyway.”

“Okay,” I finally said and followed her into the back room.

She had me look through a machine and follow a little light, and then to look to the left, and then to look to the right and see where I would see little spots of light.

And then she had me put some pads on my ears and listen to different sounds, some high, some low, and then she spoke words to me real fast and then real slow and asked me what I had understood and what I had heard.

Finally, we were finished, and I thought I’d done pretty well, because I figured I was no longer dyslexic, so I went outside to the waiting room to wait with my family. But the woman didn’t come out for such a long time that I thought maybe she’d left, or something was wrong, so I knocked on the door and her

assistant said that she was still studying my charts. And then when she came out a little while later, she looked absolutely devastated and was crying. And I don’t know why, but I started crying, too.

“In all my years of testing people for dyslexia,” she said, “I’ve had a few people off the charts. The chart is 1-20, but I’ve never had somebody so off the charts as you. Literally, according to all I know it was impossible for you to learn to speak, because you don’t hear what other people hear. And it was even more impossible for you to learn how to read. You reverse things. You take the end of a word and put it in the front and then with great difficulty you work to straighten it out so you can read it.”

Now I was really crying. “That’s true,” I said, “that’s really true!”

“Do you see rivers between the words?” she asked. “All the time,” I said. “I look at a page and I have to take a big breath to stop the rivers from coming down the page between the words from the left up high to the right down low. And you mean other people don’t see these rivers moving on the page?”

She shook her head, “No, they don’t. Oh, I’ve never had someone so far off the charts. It’s incredible, it’s a miracle that you ever learned to speak or read. And to write, to become a professional writer, is beyond my comprehension. How did you do it?”

I couldn’t talk anymore. Finally, somebody understood what I’d gone through to become a writer.

About dyslexia, I want you to know that I’m still a little bit nervous when I talk about this. I was in my mid-40s when my wife Barbara told me that a teacher told her that our two sons, David and Joseph, should be evaluated for dyslexia.

I’d never heard the term “dyslexia” and Barbara told me that this teacher explained to her that the best place to take our sons was to Long Beach, that the woman who ran the place was considered the foremost expert on dyslexia in the nation.

Well, we drove up to Long Beach and the woman took each of our boys into the back room while Barbara and I stayed in the waiting room. Then after

testing each boy, she told us that Joseph, the youngest, who was about 10 at this time, was an 8 on her charts that went from 1-20, so he would have some difficulty in reading, but not too much.

Then she told us that David who was two years older than Joseph, was a 12, so he was going to have to work twice as hard as other students to learn the same material, and yet, at his level he would still be able to finish high school and go to college and do a profession, but it was going to be difficult for him.

Well, for me all this sounded pretty good, and so I was ready for us to go. But then the woman told us that dyslexia was hereditary, and she asked if Barbara or I had trouble reading. I laughed, telling her that Barbara had been reading since before kindergarten, and I, the writer, was the one who used to have trouble, but I didn’t have any trouble anymore, and so I got up for us to leave.

But the woman now said that she’d like to test me.

This is when I began to get upset, and so I said to her that there’d be no purpose in doing this because I now knew how to read.

“I understand,” she said, “but I’d like for you to please let me test you anyway.”

“Okay,” I finally said and followed her into the back room.

She had me look through a machine and follow a little light, and then to look to the left, and then to look to the right and see where I would see little spots of light.

And then she had me put some pads on my ears and listen to different sounds, some high, some low, and then she spoke words to me real fast and then real slow and asked me what I had understood and what I had heard.

Finally, we were finished, and I thought I’d done pretty well, because I figured I was no longer dyslexic, so I went outside to the waiting room to wait with my family. But the woman didn’t come out for such a long time that I thought maybe she’d left, or something was wrong, so I knocked on the door and her

assistant said that she was still studying my charts. And then when she came out a little while later, she looked absolutely devastated and was crying. And I don’t know why, but I started crying, too.

“In all my years of testing people for dyslexia,” she said, “I’ve had a few people off the charts. The chart is 1-20, but I’ve never had somebody so off the charts as you. Literally, according to all I know it was impossible for you to learn to speak, because you don’t hear what other people hear. And it was even more impossible for you to learn how to read. You reverse things. You take the end of a word and put it in the front and then with great difficulty you work to straighten it out so you can read it.”

Now I was really crying. “That’s true,” I said, “that’s really true!”

“Do you see rivers between the words?” she asked. “All the time,” I said. “I look at a page and I have to take a big breath to stop the rivers from coming down the page between the words from the left up high to the right down low. And you mean other people don’t see these rivers moving on the page?”

She shook her head, “No, they don’t. Oh, I’ve never had someone so far off the charts. It’s incredible, it’s a miracle that you ever learned to speak or read. And to write, to become a professional writer, is beyond my comprehension. How did you do it?”

I couldn’t talk anymore. Finally, somebody understood what I’d gone through to become a writer.

About dyslexia, I want you to know that I’m still a little bit nervous when I talk about this. I was in my mid-40s when my wife Barbara told me that a teacher told her that our two sons, David and Joseph, should be evaluated for dyslexia.

I’d never heard the term “dyslexia” and Barbara told me that this teacher explained to her that the best place to take our sons was to Long Beach, that the woman who ran the place was considered the foremost expert on dyslexia in the nation.

Well, we drove up to Long Beach and the woman took each of our boys into the back room while Barbara and I stayed in the waiting room. Then after

testing each boy, she told us that Joseph, the youngest, who was about 10 at this time, was an 8 on her charts that went from 1-20, so he would have some difficulty in reading, but not too much.

Then she told us that David who was two years older than Joseph, was a 12, so he was going to have to work twice as hard as other students to learn the same material, and yet, at his level he would still be able to finish high school and go to college and do a profession, but it was going to be difficult for him.

Well, for me all this sounded pretty good, and so I was ready for us to go. But then the woman told us that dyslexia was hereditary, and she asked if Barbara or I had trouble reading. I laughed, telling her that Barbara had been reading since before kindergarten, and I, the writer, was the one who used to have trouble, but I didn’t have any trouble anymore, and so I got up for us to leave.

But the woman now said that she’d like to test me.

This is when I began to get upset, and so I said to her that there’d be no purpose in doing this because I now knew how to read.

“I understand,” she said, “but I’d like for you to please let me test you anyway.”

“Okay,” I finally said and followed her into the back room.

She had me look through a machine and follow a little light, and then to look to the left, and then to look to the right and see where I would see little spots of light.

And then she had me put some pads on my ears and listen to different sounds, some high, some low, and then she spoke words to me real fast and then real slow and asked me what I had understood and what I had heard.

Finally, we were finished, and I thought I’d done pretty well, because I figured I was no longer dyslexic, so I went outside to the waiting room to wait with my family. But the woman didn’t come out for such a long time that I thought maybe she’d left, or something was wrong, so I knocked on the door and her

assistant said that she was still studying my charts. And then when she came out a little while later, she looked absolutely devastated and was crying. And I don’t know why, but I started crying, too.

“In all my years of testing people for dyslexia,” she said, “I’ve had a few people off the charts. The chart is 1-20, but I’ve never had somebody so off the charts as you. Literally, according to all I know it was impossible for you to learn to speak, because you don’t hear what other people hear. And it was even more impossible for you to learn how to read. You reverse things. You take the end of a word and put it in the front and then with great difficulty you work to straighten it out so you can read it.”

Now I was really crying. “That’s true,” I said, “that’s really true!”

“Do you see rivers between the words?” she asked. “All the time,” I said. “I look at a page and I have to take a big breath to stop the rivers from coming down the page between the words from the left up high to the right down low. And you mean other people don’t see these rivers moving on the page?”

She shook her head, “No, they don’t. Oh, I’ve never had someone so far off the charts. It’s incredible, it’s a miracle that you ever learned to speak or read. And to write, to become a professional writer, is beyond my comprehension. How did you do it?”

I couldn’t talk anymore. Finally, somebody understood what I’d gone through to become a writer.

Victor’s Gallery

Victor’s Childhood

Step into the early years that shaped Victor’s dreams and deep cultural roots.

View GalleryYoung Victor

Explore moments of ambition, identity, and discovery in Victor’s young adulthood.

View GalleryVictor’s Friends

See the connections and friendships that added joy and strength to his journey.

View GalleryVictor’s Gallery

Victor’s Childhood

Step into the early years that shaped Victor’s dreams and deep cultural roots.

View GalleryYoung Victor

Explore moments of ambition, identity, and discovery in Victor’s young adulthood.

View GalleryVictor’s Friends

See the connections and friendships that added joy and strength to his journey.

View GalleryVictor’s Gallery

Victor’s Childhood

Step into the early years that shaped Victor’s dreams and deep cultural roots.

View Gallery

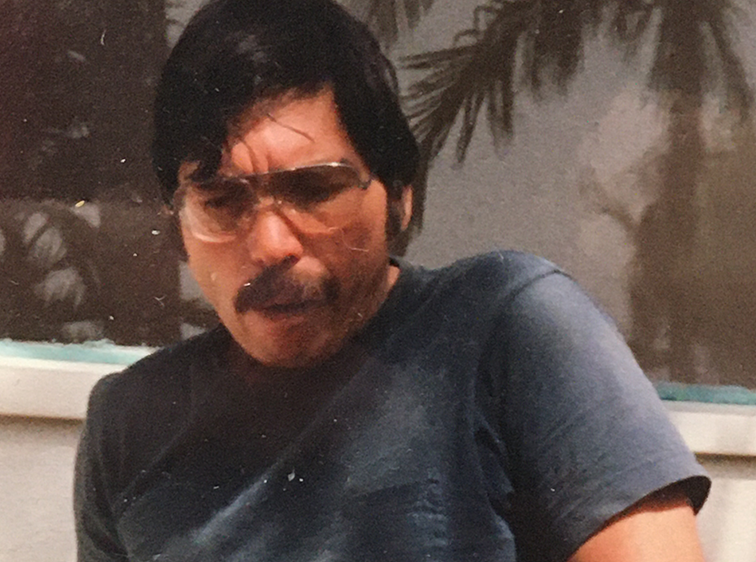

Young Victor

Explore moments of ambition, identity, and discovery in Victor’s young adulthood.

View Gallery

Victor’s Friends

See the connections and friendships that added joy and strength to his journey.

View Gallery

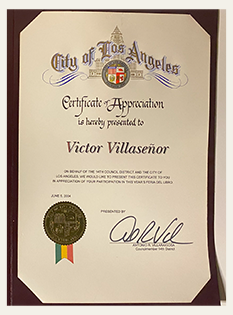

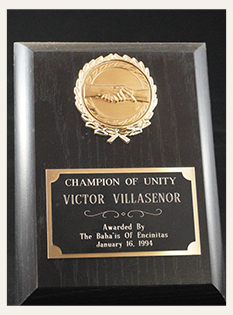

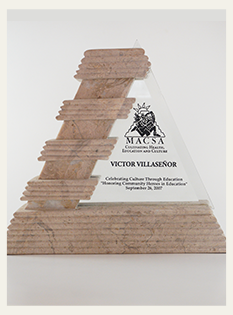

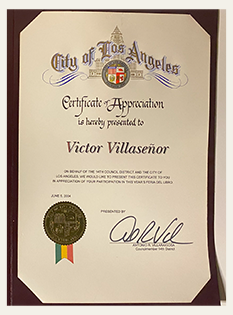

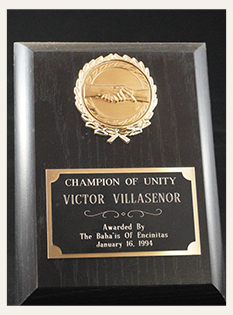

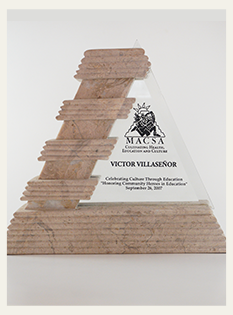

Awards & Recognitions

Awards & Recognitions